By David Liau

Disclaimer: writing a blog post has always been my greatest weakness. I’ve always been good at verbal presentation; I’ve had no problems with standing up in front of a large crowd and conveying my point. But penned artifacts are a different matter… so please bear with me!

Many opportunities in college provide people with experience in either schoolwork, social life, or graduate school life. Some may even cover two of the areas, mixing in social life with graduate school life or schoolwork with graduate school life. But in my opinion, very rarely does an event encompass all three. I’ve had the privilege of finding one activity that miraculously does combine these three topics, and in convincing fashion– my position as a research assistant in the Language and Cognition Lab.

Prior to joining, I had never heard of this lab before. On a whim, my friend Ya-han and I decided to attend a linguistics event, hoping to learn a little more about what we wanted (or didn’t want) to pursue as a career. What we didn’t know was that the supposed event was actually a lab recruitment meeting, and the presenters were graduate students.

Now I’m not going to say that this was the “fated moment” where I met my advisor and I immediately knew I was going to join her. In all honesty, I was more focused on a different lab (I can’t exactly remember which), with a secondary interest in my current lab. But when I spoke to that graduate student, whose name was Rose, I found out that they were performing experiments that needed Mandarin speakers to help in the lab. Ya-han and I both spoke Mandarin, so we thought, “why not?” and proceeded to sign up. Little did we know that joining Rose would lead to one of the most consistent events in my college life.

The first job Ya-han and I completed upon starting our internship was arguably the hardest. Our research experiment essentially aims to discern the difference between English and Mandarin speakers’ perception of time and space. These differences in culture manifest themselves within metaphors in both speech and writing. Whereas the English language is read naturally from left to right (as you are reading it now), the Mandarin language is (or at least used to be) read from top to bottom. Consequently, English gestures commonly refer to the speaker’s left as prior, and the right as future. Meanwhile, the Mandarin language is composed of metaphors that detail past as upward and future as downward (上個月, 下個月).

This seemingly minor difference between the two languages led to Rose’s research question: if the English language style allows English speakers develop a perception of the past as to the left and the future towards the right, does that mean that Mandarin speakers perceive of up as in the past and down as the future?

To test this, Rose created an experiment that would evaluate English and Chinese speakers’ interpretations of time. Each participant would see two pictures sequentially, with the second picture displaying an event that clearly occurred prior to or following the first picture. The participant would press one of two buttons, which were systematically placed “up” and “down” the keyboard, that matched the second picture’s chronological placement (before or after). This portion of the experiment is well known as the Orly task. Then, Rose would compare the reaction times of the Mandarin participants to the English participants, and determine which had a faster recognition time.

Ya-han and I oversaw the Mandarin experiment. Because we wanted to maintain the Mandarin speakers in a non-English environment, having two proctors who spoke only Chinese was the most optimal way of running the experiment. To do this, Ya-han and I compiled a list of instructions and translated them into a Mandarin script, which was modified and repeated until adequate.

Running the experiments at first was extremely challenging. Just setting up the experiment required a myriad of memorized factors—and this didn’t even include running it! But slowly, Ya-han and I got more used to the process. Nowadays, I go in every week to run participants, looking forward to the point where we have enough data to analyze.

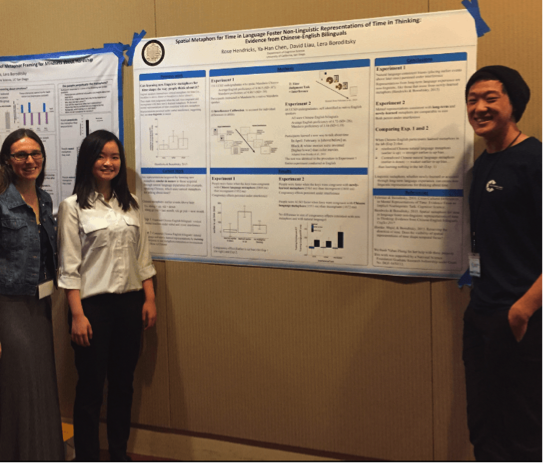

So, who are Rose and Ya-han you ask? Rose Hendricks is my graduate advisor, one of the best of the best. Not only does she excel in public speaking and linguistics research, but she’s also the loveliest person I know. I can tell that she’s truly passionate about her research on metaphors just through the everyday conversations that we have.

Ya-han is my research partner, someone who was with me since day one. We met each other through a mutual friend, and I was surprised that she was also a cognitive science major. From then on, we attended most events related to Cognitive Science together, from the initiation of our research position to presenting our findings with Rose at the Cognitive Science Conference this year. We’ve always bounced ideas off each other and used these opportunities to grow in our respective specialties.

My relationships with Rose and Ya-han deeply integrated themselves into my college career. My communication with them has been an important factor in getting through many hardships, not only in the lab but also in life. Through them and this position, I’ve gotten a slight taste of the research life.

Part of what I’ve learned about scientific research (especially in the graduate scene) is that it’s not nearly as easy as I imagined it to be. There are continually factors that impact scheduling and planning of experiments, ranging from the proctor’s availability conflicts to the participants’ unexcused absences. Then, just as a certain amount of data has been collected, there is always the impending fear of miscalculated statistics or miniscule details that render the data useless.

Not everything is bad, however. I’ve learned how to gather and analyze large amounts of data through the continuous trials of the experiment, as well as communicate properly with both fellow researchers and participants. Through training new lab assistants, I’ve developed a comfortability with being a leader when needed, as well as a more amicable character for conversing with strangers.

This lab that I’ve been part of the past two years has both broadened my horizons and sharpened my interests. I’ve received a wealth of knowledge through working with Rose and Ya-han, and I look forward to more training in data analysis and statistical tests. The first thing I think of when people ask about my college experience is unequivocally the Linguistics and Cognition Lab, and I hope it will stay so for the last years of my college journey.

This is without a doubt the best blog post I’ve ever read!!! (comment sponsored by author)

LikeLike